You can also listen to this article in the voice of own Plastic Artist Rosângela Vig:

Far from the infertile whirl,

The Benedictine, writes!! In the warmth

of the cloister, Patietly, and quietly,

He works, and insists, and persists, and sweats!!For the Beauty, twin of the Truth,

The Pure Art, the enemy of the artífice,

And the stength, and the grace in the simplicity.

(For a poet, BILAC, 2007, p.68)

These verses by Olavo Bilac (1865 – 1918) reveals the attention of the Parnassian poet over the structure. But maybe one can dare, and embody this description to many other areas where the human creativity walks, in so much Art, in many creations, made by many hands. The creator’s effort requires him, to flow from the imagination to the concrete; and from the creativity, to the rigor of the shape. It is supposed that such effort hadn’t been different to the roman artists of the Antique, with the available resources of their time. Their Art, together with the Greek, served as a foundation for the Western art and outlined the period called Greco-Roman Classical Antiquity.

It is important to mention that the Roman Empire was one of the greatest of the Antique. Their power comprised, great part of the Western and Eastern Europe in their pinnacle. According to Historians, their foundation occured in 753 B.C.. and their magnificence extended from 27 B.C.. up to the 3rd century A.D., when the struggles for power and the barbarian invasions, caused their fall in the West, in 476 d.C., when the Middle Age started. The high taxes, in their heights afforded an extravagant, and corrupt life to the elites, while they lived a “Bread and Circuses” policy. The distribution of food to the needy and the spectacles in the arenas, with the gladiators, wild animals and theater, raised the popularity of the emperors and kept the poor social classes away from the political issues.

The Culture of this people was mainly influenced by the Greek and the Etruscan that occupied the lands of Italy, in the period. In Art, shows resemblance to the idealized Beauty and harmony in shape, inherited from the Greek, since both Cultures coexisted, in the Greco-Hellenistic period. In addition, Alexander the Great, king of Macedon and disciple of Aristotle, was an admirer of the Hellenistic Culture and disseminated it through the conquered lands. The connection to the reality and the practical spirit was left from the Etruscan to the Roman Art.

It’s not known much about the Etruscan civilization, but their practical style is clear in the Roman Architecture, with the archs in the buildings, differently of the Greek, that used columns. The archs allowed a better distribution of the achitrave weight and therefore, less use of columns. Thus, the internal space use would be better. This idea was fundamental to build places capable to shelter many people, such as the temples and the amphitheaters, with bleachers, where the fights with gladiators occured, such as the Colosseum. Although the use of archs was one of the most significant characteristics of the Roman Architecture, this people also showed knowledge and mastered Civil Engineering, in building aqueducts, highways and public baths.

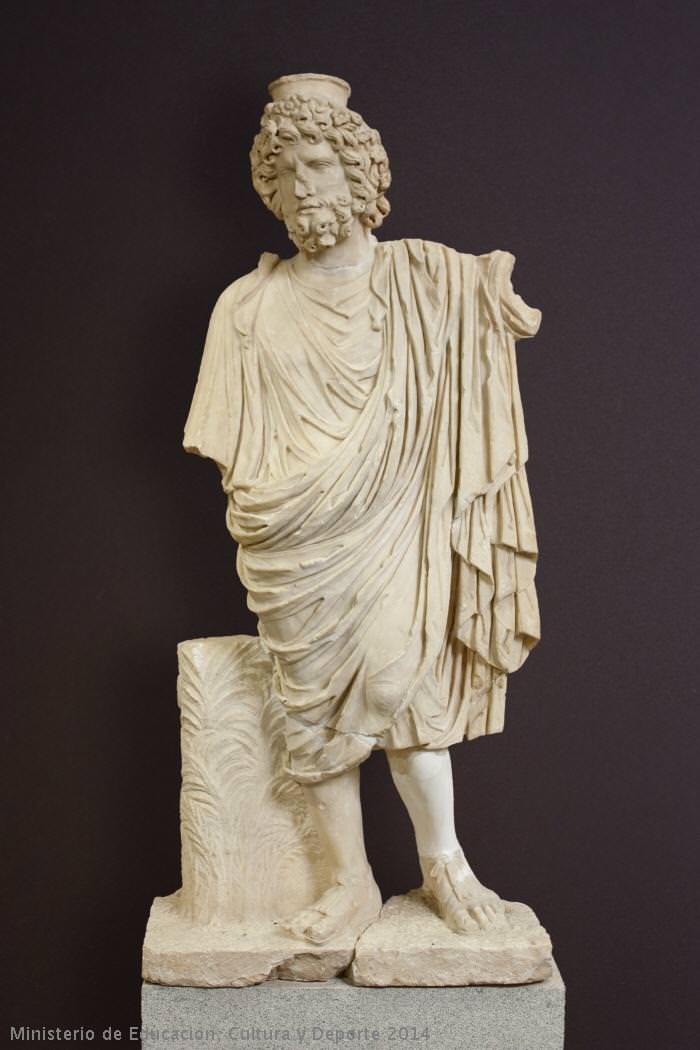

In Sculpture, the Helenistic influence is clear in the approach of the images to the human beauty patterns, on the care with the shape, the symetry and even the position of the statues. However, since the objective of the artist was to portray the reality, there is a huge realism in the Roman Work of Art, as it can be seen in the Figure 1. Among the details, there can be perceived the large amount of cloth of his garments, which unfold and seems to weigh over the character’s body. On the other hand, the practical spirit of the Etruscan can be seen in the narrative feature of the Roman Works, since they describe the wars, the conquests of the emperors, and the Mythology. The conquest of Dacia (Romania), for example, was celebrated by Trajano, with the building of a column, in Rome, known as Trajano’s Column, from 113 a.C.. and it describes the stages of this conquest, through images carved in marble.

On the field of Painting, in the field of painting, the Ancient Romans made murals, with the purpose of decorating the walls, and many were found in the 8th century, amidst the ruins of the cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum, buried after the eruption of Mount Vesuvius, in 79 a.C.. On the evolution of these paintings, there can be seen a first style, probably based on the decoration of Greek altars and temples. The gesso was applied on the walls, straight lines were carved on it, the lines moulded rectangles to give the impression of marble plates. This model changed into another with framed sceneries, that gave the sensation of perspective. This changed into another with more details, which used strong colors, such as black and red. This style also increased for a more, detailed one with tridimensional effects, and sceneries of everyday routine, Mythology and Religion, like the sculptures. These murals seemed huge walls opened, showing landscapes, with animals and people (Figures 2, 3 and 4). The Roman artists also showed ability with the mosaic, found amidst the ruins of the city of Pompeii.

The Mythology, which was the theme for many of the Roman Works of Art, was based on the Greek Culture. Many of the Gods and Godesses were the same, but had their names changed into Latin, Some were created based on the Culture of the Etruscan or the other peoples. The foundation of Rome itself was explained through the Myths of Romulus and Remus.

The Ancient, romans didn’t create their own Philosophical stream, their ethical principle was still, the one of the Greek. Among the Philosophers of this period, it can be mentioned Plotinus (205-270), who dealt with the issues of the Beauty in the Aesthetic, with a Metaphysical approach, it means, this means beyond Physics, related to a “Knowledge of Divine things" (DUROZOI, ROUSSEL, 1999, p.329). Plotinus modified the Platonism and, him though, the unachievable Beauty of Plato’s world of ideas, was not the matter, but it would be a “quality of what becomes sensitive, since a first impression; the soul pronounces intelligently over it; recognizes it, and is adjusted, over it, anyway" (PLOTINO, apud BAYER, 1993, p.75). Basically, of this thought refers to a Beauty, at Art, that is not connected to the harmony of shapes or to the material symetry, but to a deeper reason, an absolute subjectivism, found in ourselves, in the moment of contemplation. This sense for the Beauty in Art is, s disinterested interest, related to what turns men disposition into good and leads him to the right. For the Philosopher, the feelings caused by the reflections over the Beauty are associated to an awakening of love, happiness, and pleasure. It’s at the same time a message of balance and inner peace.

And, it is convenient, to complete with the message of Seneca (4 B.C.. – 65 d.C.), who believed in a happy life, linked to virtue and simplicity. For the Roman Philosopher,

Since the nature allows us to commune with all the eternity, why aren’t we away of the narrow and small passageway of time and commit entirely with our spirit to what is unlimited, eternal and shared with the superior? (SENECA, 2013, p.65)

Seneca spreaded the thought that the excess was unnecessary; the good is not what is more adorned, but what is right and fair. His Plilosophy is based on the stoicism, and is related to the Beauty of soul, which is eternal, while life is ephemeral. His inspiring message is current and proposes happiness based on self-restraint, wisdom and serenity of the spirit. Maybe to the society of the Roman Empire there was a lack of balance, but this people of the Antique left remarkable works and a great knowledge in many areas. Among this legacy, among others, such as Portuguese and all their artistic production, though many works were lost due to wars, battles and invasions.

Museo Nacional de Arte Romano de Mérida

The city of Merida, in Spain, founded in 25 b.C., after the Roman conquest and was one of the most important in the Iberian Peninsula. It was classified , in 1993, by UNESCO as World Cultural Heritage. Among the Roman architecture, there can be found the theater, the amphitheater, the bridges over the Guardiana and the Albarregas rivers, the aqueducts, the Temple of Diana, the Trajan Arch and other importante monuments.

In the city of Merida , the The Roman Museum of Merida substitutes the former Archaeological Museum of Merida from the 19th century. The current head office was projected by the Architect Rafael Moneo Vallés, and opened in 1986 with an Architecture that reminds the Roman style. The museum is considered a center for research and diffusion of the Roman Culture, with congresses, conferences, courses, exhibitions and national and international activities. In the collection there is a relevant material of the Roman Empire Art, found in excavations, such as coins, pottery, mosaics, sculptures and murals.

Source: UNESCO.

Acknowledgements:

Our special thanks to Museo Nacional de Arte Romano de Mérida.

Sign up to receive Event News

and the Universe of Arts first!

Check out History of the Museum.

Can also be taken a Virtual Visit. Check!

…

Liked? [highlight]Leave a comment[/highlight]!

References:

- BAYER, Raymond. História da Estética. Lisboa: Editorial Estampa, 1993. Tradução de José Saramago.

- BILAC, Olavo. Antologia Poética. Porto Alegre: L&PM, 2007.

- DUROZOI, Gérard; ROUSSEL, André. Dicionário de Filosofia. 3to. Edition. Campinas: Papirus, 1999.

- EAGLETON, Terry. A Ideia de Cultura. São Paulo: Editora UNESP, 2005.

- GOMBRICH, E.H. A História da Arte. Rio de Janeiro: Editora Guanabara, 1988.

- HAUSER, Arnold. História Social da Arte e da Literatura. Martins Fontes, São Paulo, 2003.

- SENECA. Sobre a Brevidade da Vida. Porto Alegre: Editora L&PM Pocket, 2013.

The figures:

Fig. 1 – Statue from the 2nd century, which represents the God Pluto. Carved in white marble, with 2,20 M High per 0,97 m width. Part of a set of statues that decorated the stage in front of a Roman theater. Photo of Lorenzo Plana Torres. Image of authorship and ownership of “Archivo Fotográfico MNAR” and piece of property of the “Museo Nacional de Arte Romano de Mérida”. (http://ceres.mcu.es/pages/Viewer?accion=4&AMuseo=MNAR&Ninv=CE00641).

Fig. 2 – Painting fresco, from the 4th century on stucco in a room, with 2,10 M high, 6,75 M length and 5,90 M width. The pictures present hunting scenes, with carts leaded by horses. The horses are the main themes of the scenes. The images are framed and ornamented with garlands and ribbons. The upper and the lower parts are decorated with geometric shapes. Photo of Lorenzo Plana Torres. Image of authorship and ownership of “Archivo Fotográfico MNAR” and piece of property of the “Museo Nacional de Arte Romano de Mérida”. (http://ceres.mcu.es/pages/Viewer?accion=4&Museo=&AMuseo=MNAR&Ninv=CE37404&txt_id_imagen=2).

Fig. 3 – Perspective Painting afresco of Fig. 2. Photo of Lorenzo Plana Torres. Image of authorship and ownership of “Archivo Fotográfico MNAR” and piece of property of the “Museo Nacional de Arte Romano de Mérida”. (http://ceres.mcu.es/pages/Viewer?accion=4&Museo=&AMuseo=MNAR&Ninv=CE37404&txt_id_imagen=1).

Fig. 4 – Detail Painting afresco of Fig. 2. Photo of Lorenzo Plana Torres. Image of authorship and ownership of “Archivo Fotográfico MNAR” and piece of property of the “Museo Nacional de Arte Romano de Mérida”. (http://ceres.mcu.es/pages/Viewer?accion=4&Museo=&AMuseo=MNAR&Ninv=CE37404&txt_id_imagen=5).

You might also like:

- First Traces of Modern Art – Abstract Expressionism in Brazil by Rosângela Vig

- First Traces of Modern Art – Expressionism in Brazil by Rosângela Vig

- Modern Art – Abstract Expressionism by Rosângela Vig

- First Traces of Modern Art – Impressionism in Brazil by Rosângela Vig

- Modern Art – Surrealism by Rosângela Vig

- Modern Art – Abstractionism by Rosângela Vig

- Modern Art – Cubism by Rosângela Vig

- Modern Art – Expressionism by Rosângela Vig

- First Traces of Modern Art – Symbolism by Rosângela Vig

- First Traces of Modern Art – Post-Impressionism by Rosângela Vig

- First Traces of Modern Art – Impressionism by Rosângela Vig

- Romanticism in Brazil by Rosângela Vig

- Romanticism by Rosângela Vig

- The Neoclassical Art in Brazil by Rosângela Vig

- The Rococo in Brazil by Rosângela Vig

- The Neoclassical Art by Rosângela Vig

- Rococo by Rosângela Vig

- How appears the Surreal Work by Rosângela Vig

- The Baroque in Brazil by Rosângela Vig

- Baroque by Rosângela Vig

- Mannerism by Rosângela Vig

- Flemish Art – Renaissance in Northern Europe by Rosângela Vig

- Renaissance by Rosângela Vig

- The Contemporary, A little about the Urban Art by Rosângela Vig

- The Naive Art – Ingénue Art by Rosângela Vig

- Middle Ages, Byzantine Art by Rosângela Vig

- Middle Ages, Romanesque Art and Gothic Art by Rosângela Vig

- Greek Art, Art History in Ancient Greece by Rosângela Vig

- The Egyptian Art by Rosângela Vig

- The Prehistoric Art by Rosângela Vig

- The beauty Art and the sublime Art by Rosângela Vig

- The Game of Art by Rosângela Vig

- The Misunderstood Art by Rosângela Vig

ROSÂNGELA VIG

Sorocaba – São Paulo

Facebook Profile | Facebook Fan Page | Website

Columnist at Website Obras de Arte

E-mail: rosangelavig@hotmail.com

The Roman Art by Rosângela Vig

The Roman Art by Rosângela Vig | Website Obras de Arte

The Roman Art by Rosângela Vig

I would like to share an article I wrote more about Roman Art in Antiquity

no link… http://t.co/mhOcjR4ysb

I want to share my article on Roman Art

Article on Roman Art by Rosangela Vig

My new article on Roman Art

http://t.co/tjUpTUJ1RZ

The Roman Art by Rosângela Vig http://t.co/gUhVdN9DHp

The Roman Art by Rosângela Vig

Roman Art by Rosangela Vig

The Roman Art by Rosângela Vig http://t.co/6iDxX2S2ZQ

Roman Art by Rosangela Vig http://t.co/6iDxX2S2ZQ

The Roman Art by Rosângela Vig

The Roman Art by Rosângela Vig http://t.co/6iDxX2iQtc